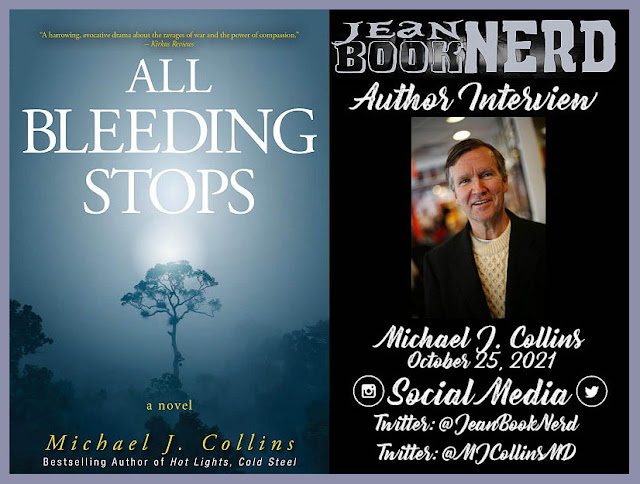

Photo Content from Michael J. Collins

Like their father, grandfather and great grandfather before them, Michael J. Collins and his seven brothers were born on the West Side of Chicago. Mike worked his way through college shoveling furnaces at South Bend Foundry during the school year and driving trucks in the summer. Following graduation from the University of Notre Dame, where he was a less-than-stellar member of the hockey team, Mike spent several years trying to figure out things he should have figured out years before. He worked as a truck driver, cab driver, construction laborer, dockworker and even did a little freelance journalism for the Irish Press in Dublin.Mike was a 24-year-old, uninspired construction laborer when a coworker asked him how much longer he was going to continue to piss away his life. That rude awakening made Mike reexamine his priorities, return to school, and pursue a career in medicine. His days as a laborer trying to get into medical school are chronicled in Blue Collar, Blue Scrubs (St. Martin’s Press). Citing a case of what he insists was divine intervention, Mike was ultimately admitted to the Loyola Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago. Upon graduation he spent five years in residency at the Mayo Clinic. His years as resident and inveterate moonlighter in rural Minnesota emergency rooms are the subject of Hot Lights, Cold Steel (St. Martin’s Press).

After completing his residency, where he served as Chief Resident in Orthopedic Surgery, Mike and his wife, Patti, moved back home to Chicago. They have lived in the same house for over thirty years, raising twelve wonderful kids, who may have aged them prematurely (especially three of you. Don’t give me that look, you know who you are!) but of whom they are immensely proud.

Since the publication of his first book in 2005, Mike has lectured throughout the country on topics relating to medicine and writing. He has served as the Alpha Omega Alpha Visiting Professor at both the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, and at the University of Minnesota. He delivered the commencement address at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine in 2016. Hot Lights, Cold Steel and Blue Collar, Blue Scrubs are on the required or recommended reading list at many medical schools and pre-medical programs.

His latest work, All Bleeding Stops, represents a departure for Mike in that it is a work of fiction. In writing this book, Mike says he hopes to raise awareness of the difficulty doctors face in learning to care for and about their patients. The very qualities—compassion, sensitivity, dedication—that lead young people to a career in medicine, are often the seeds of their own destruction. Sometimes they care too much. “A generation of young men went to Vietnam naive and idealistic,” Mike says. “They returned home broken and disillusioned—if they returned at all. We doctors are often victims of a similar fate. Like soldiers, the things we see and do are often too much to bear. And, like soldiers, not all of us make it back.”

Greatest thing you learned at school?

I remember what an eye-opening experience my Humanities Seminar was during my freshman year at Notre Dame. It was the best and the most rewarding educational experience I’ve ever had.

Tell us your most rewarding experience since being published.

I was somewhat apprehensive about how All Bleeding Stops would be received. Would readers “get” it? Would they like it? The response so far has exceeded my wildest expectations.

What are some of your current and future projects that you can share with us?

My books all have some sort of medical theme. The book I am working on now is about a man struggling with what it means to be a doctor, and what obligations this sort of commitment entails.

Can you tell us when you started ALL BLEEDING STOPS, how that came about?

My last book, Blue Collar, Blue Scrubs, was published in 2009. I started All Bleeding Stops before then, so I have been working on it for over 13 years. The book came out of a desire on my part to focus attention on the terrible price that overly sensitive doctors pay. Sometimes they simply care too much, and their empathy destroys them.

What do you hope for readers to be thinking when they read your novel?

I want readers to be entertained, of course, but I also hope to raise awareness of the difficulty doctors face in trying to care for their patients without letting that care destroy them.

What was the most surprising thing you learned in creating Matthew?

I like this question because it recognizes the fact that as a result of his work the author grows, learns, and is himself worked upon. As the character of Matthew developed during the writing of the novel, I came to understand that old adage “Virtue is its own reward” actually meant something more profound than I had imagined.

If you could introduce one of your characters to any character from another book, who would it be and why?

I think perhaps it would be to Childe Roland in Browning’s Poem “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came.” Both Matthew and Childe Roland are engaged in a noble but somewhat Quixotic quest. Both intend to accomplish something worthwhile, something meaningful, and both persevere in the face of tremendous odds.

Tell me about a favorite event of your childhood.

I was fortunate enough to have had a wonderful childhood so there is a lot to choose from. I was from a big Irish Catholic family. The feeling of belonging, of being valued and treasured meant more to me than anything.

What is something you think everyone should do at least once in their lives?

Fall in love.

Best date you've ever had?

My first date with my wife. I still recall the very first time I saw her and how it made my heart start.

What was the first job you had?

I’ve had jobs for as long as I can remember. As a kid I cut lawns, delivered newspapers, caddied, shoveled sidewalks. The first job where I actually got a paycheck was when I was 14 and got a job as a maintenance man at our local Park District.

If you could go back in time to one point in your life, where would you go?

I’d go back to the first years of our marriage when we had nothing but each other. We worked our brains out but that didn’t matter. Those were very happy years.

Most memorable summer?

The summer I met my wife. The first three times I asked her out she said no – but then later she asked me out and we took off from there.

First Heartbreak?

Sophomore year in college when my girlfriend back home dumped me. It took me a long time to get over that one.

If you could trade places with any other person for a week, famous or not famous, living or dead, real or fictional. with whom would it be?

The apostle John who rather immodestly proclaimed himself as “the disciple Jesus loved.”

QUOTES FROM ALL BLEEDING STOPS

(Sorry but you are about to get way more than you asked for. I had never done this before, so I went through the book picking out some of my favorite quotes. It was fun to do so. Just drop any ones you want)

- “Like soldiers, the things we doctors see and do are often too much to bear. And, like soldiers, some of our wounds never heal.”

- “His war begins with a quiet palette of turquoise and green; soft, shaded layers of blue and white layered like quicklime over all the darkness to follow.”

- “Bluebells in a graveyard. The rouge daub of the embalmer’s art. Perhaps it is what they eye chooses not to see that matters. An amaurosis fugax of the soul.”

- “Truth was a crystal I forged in the furnace of my own imagination and then held up to the light, twisting it, turning it, until I found that one particular refraction that served my needs.”

- “He thought he knew what it would be like to go to war: wild eyes and gritted teeth, pounding heart and churning guts. Confusion, alarm, guns, cannons, bombs.

- He never imagined war could begin with beauty.”

- “He raises his hands, stares at them in the faint light, flexes his fingers, extends them, slowly turns them front to back, back to front. The hands of a surgeon.

- He thinks he is ready - but how can he be sure?”

- “He looks at the bloodstains on his white surgeon’s shoes slowly fading from red to black as they dry in the gray morning light. He knows he has to stop letting everything get to him. Didn’t Henderson warn him? Sensitivity, compassion, idealism - those things look great on paper, Barrett, but they don’t get you very far in this sick world. As a surgeon you can’t weep and wring your hands every time you see a terrible thing. If you wanna get good, you gotta get hard.

- He wonders just how hard he has to get.”

- “They hear them before they see them, the deep thudding whump of the rotors pounding in their brains, booming in their chests. The choppers come at them, rising over the wall of trees, leaking oil, dripping blood, enlarging, becoming darker, louder, filling the sky with their deafening roar.”

- “They think death is a thing of substance and heft, a finish line, a destination, but he has found death to be a shadowy evanescence whose existence is always a matter of conjecture, of interpretation, of perspective.”

- “The slow, steady trickle of the dead and the maimed continues - unwavering, unrelenting, as if in compliance with some dark, engineered quota of human suffering over which he is forced to preside, watching all those eyes, wide with terror, fade to nothingness.”

- “The chopper sways, and she is pressed even tighter against him. The chopper rights itself, but the pressure remains. She is so close. He can smell her. He can taste her. All he has to do is raise his hands, slide them up her arms, over her elbows, across her chest, and draw her to him. But he can’t. He just can’t. Walls are all he has left. Walls are all that keep him functioning. Break down those walls, and he’ll be lost.”

- “We are all flawed, soiled, imperfect. Lawyers have no trouble with this notion. Indeed, these very conditions are what brought our profession into existence. But pity the poor physician whose raison d’etre is premised upon the notion of curing the incurable, conquering the unconquerable. What does he do when he realizes he is living a lie?”

- “On Barrett’s operating table, nineteen-year-old boys achieve communion with the warriors of generations gone by. They grasp hands and clap shoulders. A fraternity of the maimed. They know now, these shattered young men, and the knowledge hemorrhages from them, drips down the side of the table, pools on the floor. The knowledge leaps from their shattered limbs, oozes from their sightless eyes. They, too, have learned that there is no preparation for war, no defense against it, no vocabulary for it, and ultimately, no survival from it.”

- “He has never been inside the nurses’ quarters. It is strictly forbidden. He could almost laugh. Kill, murder, slaughter, hack, gouge, slash, choke - but don’t set foot in the nurses’ quarters. It is strictly forbidden.”

- “He was a complex man who revealed himself not so much by what he said as by how he said it: the struggle at times for words, the regretful sigh of wisdom come too late, the self-effacing smile, the voice of irony fading into pensive silence. At times he would look into my eyes to be certain I understood him. At times he would look away in the hope I did not.”

- “What is left when a life is over? What hovers in the air?”

- “He never knows when he will be called. There is no timetable for death. Night after night, chill winds begin to whisper through arteries and veins in Logan, in Canton, in Marietta. Youthful limbs grow stiff. Youthful hearts stutter and slow. It is time the laborers join the harvest.”

- “He can’t stop staring at her eyes. Eyes that can no longer see but still have the power to burn, to transfix. The window to the soul - except the soul behind this window has already fled. Eyes with a focal length of infinity, eyes that can see nothing and everything, eyes that narrow all life’s questions to one: Why?”

- “Awareness comes creeping tentatively from the purulent wounds of the diseased, from the burning foreheads of the febrile, from the cachectic limbs of the orphans. They come to him, day after day, the ill and the dying, the broken and the bleeding, and he cares for them, not in big ways but in the everyday manner of compassion and affection: cradling babies, wiping foreheads, sponging chests - small things that in their small ways begin to matter. The mundane rituals of mercy, of caring. Routine gestures that begin to gather the aura of grace about them.”

- “How privileged we are to practice medicine. And how privileged we are to be rewarded so handsomely for what we do. Yet how many fools finish their residencies and never recognize what they have been given, who count their remuneration solely in terms of dollars - as if dollars would make this last journey any more decipherable.”

- “She thinks she is not a good doctor because she hasn’t memorized enough textbooks or performed enough surgeries. She is so painfully aware of what she lacks, but she forgets that what we long for when we are sick - grievously sick, mortally sick - is not a cure. We know it’s too late for that. What we long for is a healing, an assurance that the human connection that seems about to be dissolved forever will somehow bridge the deep chasm we are about to cross. Scalpels can’t affect that. Textbooks can’t teach it. But compassion, the simple unaffected love of our fellow man, can. The knowledge that someone cares, that we are not alone. Gestures, touches, smiles.”

Journey to writing ALL BLEEDING STOPS

When I was a senior in medical school, working on a cardiology service at the local VA hospital, the intern on our service committed suicide. This left me shocked, saddened, and confused. What would lead a 27yo man at the start of a wonderful career to end his life? This was the beginning of my interest in the struggle doctors face in learning to care for their patients without letting that care overwhelm them. I came to realize that the very sensitivity and compassion that lead a young man or woman to a career in medicine can also be the instrument of their own destruction. Sometimes they simply care too much – and that is the story I wanted to tell in All Bleeding Stops.

Matthew Barrett, the protagonist, is drafted and sent to Vietnam as a combat surgeon. He is anxious to help the wounded soldiers brought to him for care, but despite his best intentions he can’t help everyone, can’t cure everyone. His inexperience shames him. His failures torment him. Only the love of Therese, one of the nurses, keeps him from falling apart.

After Vietnam, Matthew works for a while harvesting organs to be used for transplantation, but “stripping bodies for a living” leaves him as lost and confused as ever. Only when he travels to Biafra to care for the suffering and starving victims of the civil war does he finally come to understand the true nature of a doctor’s calling.

Matthew Barrett is an idealistic young surgeon, fresh out of residency, who is drafted and sent to Vietnam in 1967. Sensitive and compassionate to a fault, he has trouble adjusting to life as a combat surgeon. His inexperience shames him. His failures torment him. In heart-rending detail, we witness the effect that constant exposure to death and dying has on an overly sensitive soul. We watch Matthew’s gradual disintegration as he tries desperately to care for the mutilated and dying patients brought to him. His compassion brings him nothing but pain, which he tries to drown in alcohol and denial as he spirals inexorably toward psychological disintegration. Only the love of Therese, one of the nurses seems capable of saving him - but will their love survive the horrors of war?

From combat surgeon in Vietnam to transplant doctor in Ohio to relief physician in Biafra, Matthew learns that in the end love and compassion, rather than being the instruments of his destruction, are the means of his salvation.

jbnpastinterviews

Help, starring Jodie Comer. A story about the conditions in nursing homes in England in the early stages of Covid.

ReplyDeleteI just watched Dune on HBO Max.

ReplyDelete"What was the last movie you saw?" "Old."

ReplyDeleteDOWNTON ABBEY

ReplyDeleteStillwater

ReplyDeleteGreyhound

ReplyDeleteThe last movie I saw was Downton Abbey.

ReplyDeleteI recently watched the Die Hard movies, I hadn't seen any of them and my boyfriend thought that was crazy lol.

ReplyDeletea hallmark christmas movie.

ReplyDeleteI don't even remember.

ReplyDeleteOh, Kate and Leopold.

ReplyDeleteSteel Magnolias (for the 5000th time)

ReplyDelete