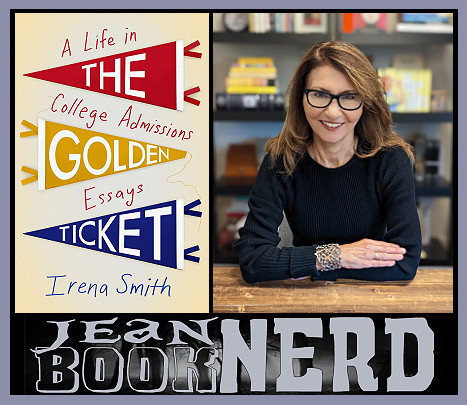

Photo Content from Irena Smith

Irena Smith is a former Stanford admission officer who currently works as an independent college counselor in the San Francisco Bay Area. She was born in the Soviet Union and emigrated to the United States with her parents in 1977, seeking asylum as political refugees when she was nine years old. There, in spite of her fierce insistence that she would never, ever learn to speak English, she went on to receive a PhD in comparative literature and to teach literature and composition courses at UCLA and Stanford before transitioning to college admissions and writing. Her writing has appeared in Mama, PhD and Art in the time of Unbearable Crisis, and her interests include reading three or four books at one time, championing the Oxford comma, and routinely infuriating her family by pointing out the difference between "less" and "fewer" at every opportunity.

Beyond your own work (of course), what is your all-time favorite book and why? And what is your favorite book outside of your genre?

Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy is probably the most exhilarating, joyfully irreverent memoir I’ve ever read. It’s got everything—saturated, hallucinatory writing that mashes together poetry and prose, an exuberantly bizarre family, a mysterious wash rag that keeps resurfacing like a cursed object in a horror movie, and a prodigal daughter who returns to the fold after “tending the pigs of liberalism, agnosticism, poetry, fornication, cussing, salad-eating, and wanting to visit Europe.” And the fold is not just any fold: it’s a rectory in Kansas City, where her father is a Catholic priest (he converted after watching The Exorcist during a deployment on a nuclear submarine. “You would convert too, I guarantee it,” Lockwood writes).

I know I’m cheating by throwing in an extra book, but I can’t leave out Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin as my favorite novel of all time. It was originally published as a series of short stories in The New Yorker, but stitched together into a novel, these stories make an extraordinarily cohesive whole. On the face of it, the novel is an academic satire, but it’s also an artfully constructed meditation on displacement, grief, art, nostalgia, loyalty, and resilience, and its protagonist—eccentric, bumbling, lovable Russian lecturer Timofey Pnin—remains stubbornly kind even in the face of misfortunes that range from the absurd to the heartbreaking.

Outside of my genre, I love Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire— an elegant, lucid explanation of plant biology and evolution. I’ve never considered myself a science person, but The Botany of Desire helped me appreciate just how compelling science could be. Pollan traces how four plants —black tulips, apples, potatoes, and marijuana—have evolved to appeal to the human desire for beauty, sweetness, nourishment, and intoxication. I mean, if that’s not masterful plotting, I don’t know what is.

Tell us your most rewarding experience since being published.

I know I’m cheating by throwing in an extra book, but I can’t leave out Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin as my favorite novel of all time. It was originally published as a series of short stories in The New Yorker, but stitched together into a novel, these stories make an extraordinarily cohesive whole. On the face of it, the novel is an academic satire, but it’s also an artfully constructed meditation on displacement, grief, art, nostalgia, loyalty, and resilience, and its protagonist—eccentric, bumbling, lovable Russian lecturer Timofey Pnin—remains stubbornly kind even in the face of misfortunes that range from the absurd to the heartbreaking.

Outside of my genre, I love Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire— an elegant, lucid explanation of plant biology and evolution. I’ve never considered myself a science person, but The Botany of Desire helped me appreciate just how compelling science could be. Pollan traces how four plants —black tulips, apples, potatoes, and marijuana—have evolved to appeal to the human desire for beauty, sweetness, nourishment, and intoxication. I mean, if that’s not masterful plotting, I don’t know what is.

Tell us your most rewarding experience since being published.

Several people who read the ARC have confided that they, or someone close to them, had struggled with mental illness. I’m discovering that pulling back the curtain on my own imperfect life gives others the encouragement to do so as well.

What was the single worst distraction that kept you from writing this book?

What was the single worst distraction that kept you from writing this book?

Apart from the demands of everyday life, The New York Times Spelling Bee.

Has reading a book ever changed your life? Which one and why, if yes? Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I first read it as a nine-year-old, which was probably far too young to read a novel about the devil paying a visit to Moscow in the 1930s, but there were special circumstances: my parents and I were living in Rome after emigrating from the Soviet Union. My parents had packed The Master and Margarita in one of our four suitcases, and while we were waiting to be admitted to the United States as political refugees, I read it—devoured it, really. It haunted me for months, and much later, when I was a junior in high school, I set out to translate it from Russian into English (as an insufferable 16-year-old, I found the two existing translations inadequate). About three paragraphs in, I began to understand that translation was hard work; six pages later, I gave up. But something compelled me to bring those six inexpertly typed pages with me to UCLA, where I showed them to a Russian literature professor who showed them to Michael Heim, the most preeminent translator of his generation. Michael Heim asked me to visit him in office hours, spent an hour discussing the nuances and challenges of literary translation (with me! an 18-year-old who knew nothing!), and became a cherished mentor. I never did finish the translation, but I’ve become a Master and Margarita evangelist. The weirdest thing? Just about everyone I’ve recommended it to has come back with stories about how the book has changed their life in some way. I’m convinced that it has some kind of uncanny power.

Why is storytelling so important for all of us?

Has reading a book ever changed your life? Which one and why, if yes? Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I first read it as a nine-year-old, which was probably far too young to read a novel about the devil paying a visit to Moscow in the 1930s, but there were special circumstances: my parents and I were living in Rome after emigrating from the Soviet Union. My parents had packed The Master and Margarita in one of our four suitcases, and while we were waiting to be admitted to the United States as political refugees, I read it—devoured it, really. It haunted me for months, and much later, when I was a junior in high school, I set out to translate it from Russian into English (as an insufferable 16-year-old, I found the two existing translations inadequate). About three paragraphs in, I began to understand that translation was hard work; six pages later, I gave up. But something compelled me to bring those six inexpertly typed pages with me to UCLA, where I showed them to a Russian literature professor who showed them to Michael Heim, the most preeminent translator of his generation. Michael Heim asked me to visit him in office hours, spent an hour discussing the nuances and challenges of literary translation (with me! an 18-year-old who knew nothing!), and became a cherished mentor. I never did finish the translation, but I’ve become a Master and Margarita evangelist. The weirdest thing? Just about everyone I’ve recommended it to has come back with stories about how the book has changed their life in some way. I’m convinced that it has some kind of uncanny power.

Why is storytelling so important for all of us?

Storytelling is what makes us human, and it’s what connects us to other humans. Thousands of years ago, people gathered around a fire and told stories; now, people gather around digital hearths (Reddit, Facebook, Twitter) and tell stories there. It’s such an elemental need, to reflect or to understand or to transform the world through words, and even in our current moment, which often seems hopeless and full of vitriol, storytelling is how we understand ourselves and others. Without the imaginative leap we make when we tell or read stories, the world would be a far duller place.

In an interview, Nabokov once said that he imagined poetry began “when a cave boy came running back to the cave through the tall grass, shouting as he ran, ‘Wolf, wolf,’ and there was no wolf. His baboon-like parents, great sticklers for the truth, gave him a hiding, no doubt, but poetry had been born—the tall story had been born in the tall grass.” I love that.

TEN RANDOM FACTS ABOUT THE GOLDEN TICKET

In an interview, Nabokov once said that he imagined poetry began “when a cave boy came running back to the cave through the tall grass, shouting as he ran, ‘Wolf, wolf,’ and there was no wolf. His baboon-like parents, great sticklers for the truth, gave him a hiding, no doubt, but poetry had been born—the tall story had been born in the tall grass.” I love that.

TEN RANDOM FACTS ABOUT THE GOLDEN TICKET

- Finding the right title was at least as difficult as naming a baby. Among the contenders: The Book of Complaints and Suggestions, Contingency Plans for Unexpected Occurrences, and You Don’t Know the Half of It.

- After working on the book haphazardly for nearly 20 years, I spent 72 hours in a frenzy of writing and editing to pull the pieces into some kind of coherent order after my agent (who was not yet my agent) asked me to send her the manuscript. There was no manuscript per se, and because it was a Friday, I asked her (all casual-like) if I could have the weekend for final touches (while screaming internally). Evidently whatever I did worked, because she agreed to represent me.

- I reread Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory recently and was astonished by the parallels between terrible parental behavior at Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory and terrible parental behavior among some parents of high school seniors applying to highly selective colleges.

- In a chapter toward the end of the book, I describe walking from Trader Joe’s to Whole Foods through old Palo Alto and borrow heavily from the motifs and images in The Odyssey. Only recently, I noticed that there’s a Montessori preschool a half a block from my route called Odyssey Preschool.

- I’ve applied to Stanford—which casts a long shadow over my book—twice, once for undergrad and once for graduate school. I was rejected both times.

- I turned out OK anyway.

- Number of times my agent pitched the manuscript to traditional publishers: 70.

- Number of times the manuscript was rejected: 70.

- It worked out in the end. (Big shout out to Brooke Warner and She Writes Press!)

- I was an avid watcher of Gilligan's Island (described in an early scene in the book). What’s not described is one of my favorite moments, when Mr. Howell III, a stuffy, Harvard-educated millionaire, gasps, “Heavens, Lovey, a Yale man!” after the castaways capture a snarling, loincloth-clad jungle native. My parents and I had been in the US for about a year at that point, and I had no idea why this was hilarious—only that it was. That I found this scene funny as a ten-year-old not yet fully fluent in English was a clear sign that I was destined to be a college admissions counselor.

What's your most missed memory?

My paternal grandmother rolling out paper-thin sheets of dough on the kitchen table to make homemade bowtie pasta for kasha varnishkes. She always gave me a small piece of dough to play with, which we would ceremoniously bake in the oven and which, if memory serves, always ended up an inedible hard lump.

Which incident in your life that totally changed the way you think today?

Having my first child. I was writing my dissertation at the time and I was pretty sure I knew everything about everything. It turns out that being able to marshall psychoanalytic theory to discuss physical and semantic displacement in the novels of Nabokov and James does not necessarily translate into being a competent parent.

When you looked in the mirror first thing this morning, what was the first thing you thought?

When you looked in the mirror first thing this morning, what was the first thing you thought?

Is it time to get bangs? It might be time to get bangs.

What was your favorite subject when you were in school?

Without question, English.

What is your most memorable travel experience?

Driving to see the Grand Canyon with my parents the summer before eighth grade. In August. In a 1973 Plymouth Satellite with vinyl seats and no air conditioning. We had been in the United States for three years after emigrating from the Soviet Union, and everything felt so mind-blowingly exotic. And I mean everything—the Grand Canyon, the enormous cacti reaching heavenward along the freeway, our first taste of a BLT in a Denny’s outside of Flagstaff.

Palo Alto, California, is home to stratospheric real estate prices and equally high expectations, a place where everyone has to be good at something and where success is often defined by the name of a prestigious college on the back of a late-model luxury car. It’s also the place where Irena Smith—Soviet emigre, PhD in comparative literature, former Stanford admission officer—works as a private college counselor to some of the country’s most ambitious and tightly wound students while her own children unravel. Narrated as a series of responses to college application essay prompts, The Golden Ticket combines sharp social commentary, family history, and the lessons of great (and not so great) literature to offer a broader, more generous vision of what it means to succeed.

jbnpastinterviews

Best date I ever had was meeting someone on vacation and then joining him for local cuisine and a tour of the area.

ReplyDelete