Photo Credit: Jeannine Pound Photography

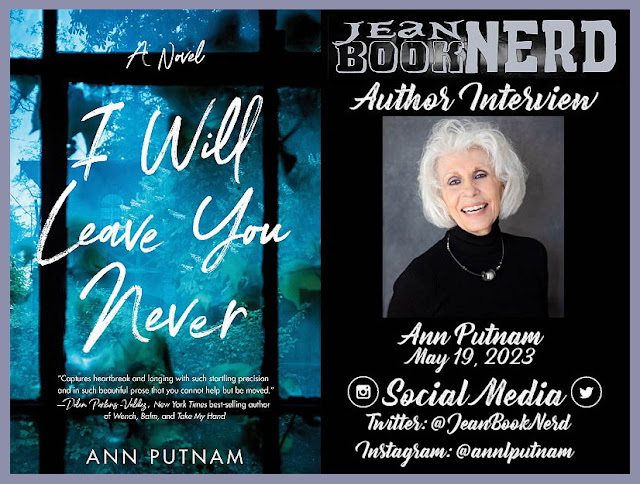

ANN PUTNAM is an internationally-known Hemingway scholar, who has made more than six trips to Cuba as part of the Ernest Hemingway International Colloquium, sponsored by the Cuban Ministry of Culture. Her novel, Cuban Quartermoon, came, in part, from those trips, as well as a residency at Hedgebrook Writer’s Colony. She has published the memoir, Full Moon at Noontide: A Daughter’s Last Goodbye (University of Iowa Press), and short stories in Nine by Three: Stories (Collins Press), among others. Her literary criticism appears in many collections and periodicals. She holds a Ph.D from the University of Washington and has taught creative writing, gender studies and American Literature for many years. She has two forthcoming novels, and lives in Gig Harbor, Washington.

When did you realize you had a creative dream or calling to fulfill?

In the 5th grade, my favorite card game was Authors. In the 7th grade, I said I wanted to marry a writer until I realized that, as Joyce Carol Oates would go on to say, “Being Lewis Carroll was infinitely more exciting than being Alice, so I became Lewis Carroll.” I wanted to be a writer, not marry one. So I guess this is something I have pretty much always known about myself.

My first literary work was a play, “Jody and Caroline Go Berry Picking,” in which Jody is bitten by a rattlesnake, and Caroline must run for help. This is so curious right now, as the novel I’m currently working on includes a poisonous snake named Ruby as one of the “characters.”

It’s Georgia, 1939. A drowning, a mysterious healing, a cottonmouth snake, and Virginia Woolf, ecstasy and terror. I’m writing about all of them. I don’t quite know how this happened but all I can say right now is, thank you! At the heart of the book is an inexplicable boating accident—three went into the water, only one survived. Lily O’Connor, the survivor and main character, experiences both the terror and ecstasy of love. Yet all characters suffer loss of one kind or the other. There is a villain to be sure, with auburn hair and ice-blue eyes, but he too, has loss in his benighted, damaged heart. In the end, this book takes the reader from ordinary life to a place as far from the ordinary as one could get, only to find that it is as profoundly familiar as it is strange. The book asks: what can I believe in if everything I have loved is lost? It’s called The World in Woe and Splendor.

Now how did I get from that great question to snakes? I’ve only just now connected that first literary work to this latest one. So thank you for this question!

What advice would you give to someone who wanted to have a life in writing?

Find a story that needs to be told and you are the only one to tell it. After this story is done, find another and another. There is no end to it if you are living the life of a writer. And mostly I would say that it isn’t the final product and certainly not publication, that is the real thing. It’s the daily, in and out, up and down of it, the discoveries and false starts and surprises and despair of it you must love more than anything.

For me, being a writer is existential. It goes to the bone. If I’m not writing, things aren’t right with me or with the world. It’s something I can’t stop doing. Though some days I’d give pretty much anything for one revelatory word. Okay, for one serviceable word. And even that sometimes doesn’t come. Still, the next day I’m at it again. And the day after that, and after that. And somewhere in there a word, or a phrase, maybe a whole line, is so lovely and so original I can’t believe it came from me.

The writer, Marge Piercy, wrote: “The real writer is one who really writes. Talent is an invention like phlogiston after the fact of fire. Work is its own cure. You have to like it better than being loved.”

Can you tell us when you started I Will Leave You Never and how that came about?

I began it on a drive home from Glacier National Park where we'd taken the children, not knowing a grizzly bear had just killed three people. The experience of the bear was far more real to me than to them. They thought it was a grand adventure and loved wearing bear bells tied to their shoes. The terror of that bear has never left me, nor the sense that I would never be big enough or brave enough to protect my children from it wherever it was. But it began my thinking about motherhood and mortality, safety and peril—and thus the urgency of writing this story, which as it turned out has no actual bear in it at all

That experience wound up as a short story, called “Zoe’s Bear,” but the novel that came out of it had no bear in it at all, except for a giant stuffed polar bear my protagonist buys in a hospital gift shop. But then “Zoe’s Bear” became another story, then another yet again, my constant companion over the miles and years. But throughout the revisions, it retained the shadow of the bear as a metaphor for mortality in various forms both strange and familiar. I wrote it at my desk at home, on planes, in emergency rooms, doctor’s offices, PTA meetings, gymnastics and track meets, traffic lights. It took days, months, years, and went through many iterations, before it finally became, I Will Leave You Never.

Has reading a book ever changed your life? Which one and why, if yes?

I was a junior in high school, being interviewed for an Honors class in English. The man interviewing me noted that I’d come into his office carrying my books, and the one on top was Spartacus by Howard Fast.

“Did you know Howard Fast was a Communist?” he asked.

Even then, outside the question, I knew he was trying to unsettle me.

“No,” I said, “I didn’t know that.” I loved that book no matter what politics Howard Fast had. It wasn’t till later that I learned how he was blacklisted for years.

“Why are you reading it?” he wanted to know. I had little to say, other than, “I really liked the story.”

“Well, you should know why you are reading it.”

I hated him then and now, as I’m remembering this.

I stood up to leave and caught the edge of my skirt on the back of the chair and ripped half my skirt off.

I watched him turn red as I scooped up my dangling skirt with my free hand. I think he said, “Oops.”

“I loved this book,” I said again, as I went out the door.

Turned out I qualified for Honors English, but it also turned out that I had to choose between Honor English and Band, as they were given at the same time. I was the school’s drum majorette (i.e. half-time baton twirler) and I had to choose between books and wild applause. I chose Band. So I never had classes in the great books, never read the classics in a class. I never read the books I should have. Still, I read all the time. And didn’t do too badly on my own.

I was a sophomore in college, taking an American Literature course, which gave me my first encounter with Ernest Hemingway. We were reading A Farewell to Arms. I couldn’t stop reading it until I came to the last sentence. “After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.” I cried for a week. I cried for Catherine and her dead baby, for Frederick, alone in the hotel in the rain, for all losses, great and small. And I knew like a thunderbolt that this is what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to read books that moved me like that and talk about them and write about them. And I knew I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t know then that I would go on to graduate school in English, thinking that Hemingway was probably only a teenage crush I’d grow out of any day.

But I didn’t. My journey with Hemingway led to a doctoral dissertation on Hemingway’s short stories. And that led to a life as an academic, where, indeed, I could talk about works that moved me, and would move my students. It also led to six trips to Cuba as part of a Cuban Hemingway Colloquium, and that in turn, led to my novel, published this past summer called Cuban Quartermoon, which includes Hemingway as a ghostly and profound presence.

So yes, I’d say A Farewell to Arms was a book that pretty well changed my life.

Why is storytelling so important for all of us?

What an important question! It would take pages to begin to do it justice. Still, here I am, giving it a try. As a fiction writer, who often must “lie” to tell the greater truth, I can say that all stories matter. As a writer, I must tell them, theirs and mine, with as much courage and honesty as I can. Without our stories, we don’t know who we are. We often lead ‘‘lives of quiet desperation” as Thoreau had said. Stories are our identity, our healing. Our way of being on this earth.

Bonnie Friedman explains it best in Writing Past Dark. She’s quoting Oscar Wilde: “To deny one’s own experience is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life. It is no less than a denial of the Soul.” Then she writes: “How fine it would be to fully claim our eyes and ears and mouths, to say, ‘This is what I see. This is what I hear. And this is how I say it. Listen: I say it like this.’”

Mary Oliver wrote, “We have to be each other’s storytellers—at least we have to try. Still, it is like painting the sky. What stars have been left out. . . ?” I have a good friend named Kathy, who often doesn’t see the significance of her own stories. I have tried to tell them.

Kathy always looked out for her elderly neighbor across the street. She’d be sure each morning before she went to work, that Trudie’s kitchen light was on. One day the kitchen was dark. She took the spare key and let herself in. “Trudie? Are you all right?” She found her in the bathroom. She had fallen and struck her head and bled to death. It was a terrible story. But that’s not the story I’m trying to tell. After the ambulance left, my friend carried her mop and sponge across the street to clean the awful blood, so that Trudie’s daughter wouldn’t have to see it. My friend told it so matter-of-factly, I remarked on it and she said, “It’s only what anyone would do.” But they wouldn’t. I don’t know if I would have.

We need to be each other’s storytellers. We need to tell our own stories, but we also need to tell others’ as well. Sometimes a person will do something so essential to who they are, so revelatory and extraordinary, it’s beyond their own recognition. And so someone must bear witness. It’s what we must do for each other. It’s what fiction writers do in shaping a story from their lives as they have lived them.

Writing Behind the Scenes

Don’t we always want to know how a work came into the world? What’s the magic trick? Maybe with some incense, chants, a candle lit, a shaman or two? Nah. I pretty much always begin unceremoniously, with a little notebook or a spiral set of 3x5 cards where I write words and phrases up and down, and all around. Anything too linear and I frighten myself to death. Little whirls and spins of words and phrases scattered over a little piece of paper and I’m braver than I ever thought I could be. Then I do a cluster. I put a trigger word in the center of a circle and draw spokes of words coming from them and then other words coming from other spokes, not knowing how any of it fits together. But it’s the only way I can start without terrifying myself. The idea of starting a novel, holy moly! I couldn’t do that. I can only write these little snippets of images/words here and there. But when I find myself writing a phrase or word on my wrist, or my car registration or cereal box or in the margins of a book I’m reading because I can’t find paper fast enough, I know I’ve plunged headfirst into the stream.

And then comes the music. At first a mood—then a theme for each character, drawing mainly upon movie soundtracks. Sweeping, dark, poignant music floating in my head and heart completely divested of the movie from which it came, is my muse. The English Patient, The Ghost Writer, Million Dollar Baby, The Hours, E.T. to name a few. And that sends me spinning into free-writing, which often begins with: “I have no idea what I’m doing” until, suddenly, I do, and find I’m not free-writing anymore, but I’m in story, and then in a working rough draft. It’s that draft I spend months, maybe years revising: cutting, polishing, deepening.

Along the way, however, I really don’t know what the next step will be, let alone the next chapter, and certainly not the ending. I believe I changed the ending of I Will Leave You Never almost seismically, at least three times. And of course, with the changes in the ending, came changes in the beginning and changes in between. For example, when I was beginning my second draft, I suddenly knew that the story I was trying to tell had an arsonist in it. That changed the ending, but it also changed the beginning and everything else along the way. I wove a new strand of yarn into the existing piece—up and down, round and round, from one end to the other (I have never knitted anything, so this metaphor is pretty much falling apart.). And when I held it up, I could see that the new strand of yarn was a color I had never seen before, and that color changed the tint and hue of the whole piece in some sudden and miraculous way.

What is the first job you have had?

Teaching baton twirling in a parks & recreation program

Best date you ever had?

A car ride to the South Hill of Spokane Washington to see the Christmas lights. We never found the Christmas lights, but we found each other.

What is your most memorable travel experience?

Trip to Pamplona, Spain to see the bullfights. On the last night of the Fiesta, a Basque terrorist pulled a stiletto on me and demanded the film in my camera.

First Love?

I fell in love with him on that first date, searching for the Christmas lights. So my first love became my true love and my husband and father of my three children.

Camp Stories?

First and only camp experience summer of the 5th grade. Every day at around 4 in the afternoon I would be overcome with the most wrenching homesickness. I thought I would die. I phoned my parents to come and get me and they said, “NO.” What? “Just try to tough it out. It will be good for you.” It wasn’t until after I had children that I realized how hard this must have been for them.

I’d spent a glorious day in the lake, jumping off the dock, perfecting my dive. But four o’clock would come and I’d be just wrenched apart. It felt like terror. And every day about the same time, my stomach would roil, my head would spin and I’d start to cry and couldn’t stop. After dinner the crying stopped. At bedtime I was fine. Years later I was diagnosed with hypoglycemia! All I needed at four o’clock was not my parents at all, but just a good hearty snack.

What do you usually think about right before falling asleep?

Anything, but how hard it is to fall asleep? I am of those who walk by night. I went to a sleep clinic once and sat in the waiting room where everyone was fast asleep in their chairs. When it came time to see the doctor, I said, “Please give me what they’ve taken.” And the doctor said, “Oh, those are people with narcolepsy.” So when I get into bed, I count to 10 any number of times. Then in my mind, I go through my weight workout one exercise at a time. I might say a prayer: “I am not worthy that you should come under my roof. Say but the word and my soul shall be healed.”

What is your greatest adventure?

Greatest is a tough one. Maybe there should be one adventure that inevitably and always rises quickest to mind. But think I’d need a list. Childbirth? Travel? My life as a writer? And Adventure? Adventures can be inward and soulful as well as outrageous and daring.

Right now, the thing coming to mind is my “adventure” teaching writing in a women’s maximum-security prison.

It was the coiled razor wire and my claustrophobia that was the adventure. As was getting through security wearing my underwire bra, which always set it off. But more, it was the yearning, the hunger my students had for learning, for language, for words, for books, for ideas. Some of them had been imprisoned for a decade or more. Some of them had killed someone. All of them wanted a life they’d never have. I was stunned at how much was asked of me and how little I had in me to give.

We were reading Ann Patchett’s Bel Canto, which of course, describes the lives of people held hostage in Peru, for months. They didn’t know if ever they would be free. My students knew right away what that was like. “It’s like being put in the hole,” they said. The place you’re sent when you break the rules. And the thing is, you can’t bring any of your own possessions, nor are you told how long you’ll be there. Purgatory for eternity, or so it seemed. Even imagining it took my breath away.

What is one unique thing you are afraid of?

Nuns!

Nuns in their habit are terrifying to me. When I was three, I was hospitalized for double pneumonia. In those days parent couldn’t spend the night with their child. It was a Catholic hospital, and the nurses were nuns. I had to have penicillin injections every three hours night and day for a week. One nun would come into my room and scoop me out of my bed, while the other nun gave me the shot. I would see the shape of the nun’s habit against the light in the hall coming toward me and I would begin screaming. Even today, a nun in the old habit will give me the chills.

Nuns!

Nuns in their habit are terrifying to me. When I was three, I was hospitalized for double pneumonia. In those days parent couldn’t spend the night with their child. It was a Catholic hospital, and the nurses were nuns. I had to have penicillin injections every three hours night and day for a week. One nun would come into my room and scoop me out of my bed, while the other nun gave me the shot. I would see the shape of the nun’s habit against the light in the hall coming toward me and I would begin screaming. Even today, a nun in the old habit will give me the chills.

In the middle of a perilous drought in the Northwest, an arsonist begins setting fires all around. It gives Zoe Penney nightmares about her home—seated right next to tinder-dry woods—rising up in explosions of fire, as well as haunting dreams of a little boy deep in the forest.

Winter brings the longed-for rains but also a cancer diagnosis for Zoe’s husband, Jay, which plunges the family into disbelief and fear. The children lean in close to their parents, can’t stop touching them. As Jay’s treatment begins, nature lets loose with strange and startling encounters, while a shadowy figure hovers about the corners of the house.

First, Zoe’s fear turns to anger: How can I love you if I am to lose you? How can I live in joy when the sky is falling? But she gradually learns that it’s possible to love anything, even terrible things—if you can love them for what they are teaching you.

jbnpastinterviews

0 comments:

Post a Comment